"Faithful in little, faithful in much…."

"Faithful in little, faithful in much…."

A letter by Fr Joseph Chalmers Prior General of the Carmelites on the occasion of beatification of Fr Hilary Januszewski, O.Carm.

13 June 1999

Dear brothers and sisters in Carmel,

The Holy Father, Pope John Paul II, during his next apostolic visit to Poland, will beatify 108 martyrs who were victims of the nazi persecution during World War II. Among them is our brother, Father Hilary Januszewski.

Dachau and the Carmelites

Along with some magnificent human, scientific, social and political achievements, the twentieth century, now drawing to a close, will leave us with a number of dreadful names: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Verdun, Rwanda and others, each an example of the horror, barbarity and disregard for humankind which has also marked this century. Dachau is one of those names. It was the first concentration camp opened by the national-socialism, back in March 1933, on the premises of a former arms factory. It was also practically the last one to be freed, on 29 April 1945. The name of this noble barbarian town, near Munich, famous for its nineteenth-century school of painting and the hospitality of its people, became forever linked to the Lager (concentration camp).

On 16 July 1942 an unusual clandestine ceremony was held to celebrate the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Several Carmelites, from different parts, were imprisoned at the camp at the same time in the huts reserved for the clergy. That morning, at dawn, before setting out for their forced labour, they joined hands to celebrate with joy, despite the appalling nature of the circumstances, the fact that even there they could be and persevere sub tutela matris.

One of them was Father Titus Brandsma, a Dutch Carmelite, journalist and lecturer at the University of Nimega (of which he was Rector Magnificus), imprisoned for defending the rights of the Catholic press against the forces of domination and for trying to save a group of Jewish children. He was beatified by John Paul II in November 1985. One of his companions was Brother Raphael Tijhuis, who was with him during the last days of his life and who was the main witness of these dramatic events.[1]

Father Albert Urbanski was also there. He was a Polish Carmelite who was to write some beautiful letters to the Curia General in Rome shortly after the camp was liberated in May 1945, describing his experiences over the years in which he was deprived of his freedom and the most basic rights. He set an example by putting himself at the service of the Order right from the beginning.[2] Urbanski wrote one of the first accounts of the camp and the priests’ life there.[3] After the War, he did some marvellous work in several positions of responsibility. He was provincial from 1964 to 1967. He was the first president of the Studium Josephologiae Calissiae (under the Polish Studium Mariologiae).[4]

Several other Polish Carmelites were imprisoned at the camp. Some of them survived the hell of Dachau, although they came out of it severely marked by the experience, both physically and psychologically. Others, however, lost their lives there. Among them we find Father Leon Michail Koza, who died on the vigil of Ascension Day in 1942 through exhaustion owing to the tough labour in the fields;[5] Father Szymon Buszta, who died a few weeks after Father Koza, also as a result of physical and psychological exhaustion [6] and Father Bruno Makowski.[7] Together with them, we should mention G. Kowalski, who died in Auschwitz in November 1940, while waiting to be transferred to Dachau [8].

Father Hilary Januszewski, the one who will soon be beatified by Pope John Paul II, was also there. He is the second Carmelite of this century to be beatified, which is a source of deep satisfaction for the whole Carmelite family.

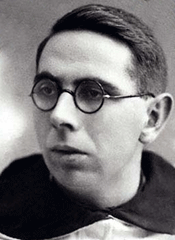

Father Hilary Januszewski

Father Januszewski was born in Krajenki on 11 June 1907. He was christened Pawel and educated in the Christian faith by his parents, Martin and Marianne. After going to school in Greblin (where the family lived from 1915), he continued his studies at the secondary school (Gimnasium) in Suchary, which he had to leave later because of financial difficulties in the family. After periods at other schools, he went to Krakow, where he did a number of courses (including correspondence courses) and joined the Order of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel in September 1927, whereupon he changed his name to Hilary. After his noviciate, he took his vows on 30 December 1928 and moved to Krakow to do his studies for the priesthood. After these studies he was sent to Rome to study at St. Albert’s International College. There he lived with Carmelites from all over the world who were concerned with how the situation in Europe was becoming increasingly complicated and how tension was rising all the time. The young Hilary proved to be a silent and prudent man, who loved studying. People could sense in him a deep inner life and a wealth of spiritual experience, as some of his colleagues, including Prior General, Father Kilian Healy [9], were to indicate later on. He was ordained on 15 July 1934. In Rome, he came into contact with a generation of Carmelites who were to mark the history of the Order during this century: Xiberta, Brenninger, Esteve, Grammatico, Driessen and others.

Upon his return to Poland, he was appointed lecturer in Dogmatic Theology and in Church History for the students of the Polish province in Krakow. In 1939 he was appointed Prior of that community by the provincial, Father Eliseo Sánchez Paredes, one of the Spanish Carmelites who had been sent to Poland to help in the restoration of this province.

World War II was to jeopardise all the hopes and projects of the young prior. On September 1, 1939, after several months of widespread international tension, Germany declared war on Poland. It was the beginning of a terrible month in the recent history of Poland. Twenty days later, Soviet troops launched an attack from the East. A weak Polish army surrendered on both fronts at the end of that month. Poland was once again humiliated and divided. Mass deportations, destruction, annihilation of Jewish communities followed in quick succession. The Polish clergy did not escape this persecution. A year after the invasion, the invading forces ordered the arrest of large numbers of monks and priests. The Carmelites in Krakow were particularly hard hit: on September 18 A. Urbanski, A. Wszelaki, M. Nowakowski and P. Majcher were all arrested, to be followed shortly afterwards by the prior of the community H. Januszewski, who offered to go instead of P. Konoba, who was older than him and sick. Father Januszewski acted heroically without stopping to consider the consequences of his action, guided by his conscience and his Christian and religious values, by what he considered to be his obligation as the head of a Carmelite community. He was arrested and, after some time at the Montelupi prison in Krakow and several concentration camps, he ended up at Dachau.

During the severe winter of 1945, news began to filter through that the German army was growing weak and that there was a possibility of retreat and even of freedom. Life at the camp had become unbearable. In addition to the normal conditions, there were constant threats of bombings and reduced rations. The kapos (prisoners in charge of working parties) were continually on edge, intensifying beatings and other forms of repression.

Hut 25 was being used to group together, in the most inhumane conditions, all the prisoners with typhus fever, who were constantly growing in number. The camp authorities offered the Polish priests the opportunity to put their "theories" of Christian charity into practice and look after the typhus patients. Freedom was by then imminent and the risk of death in the wretched hut 25 was very high. However, the silent Carmelite was one of the first volunteers.

What he said to his friend Father Bernard Czaplinski (later the Bishop of Chelm) shortly before he set off for the hut leaves one very moved even today: You know I won’t come out of there alive….[10]

Sure enough, Father Januszewski never left Dachau alive. After 21 days serving the sick, he died of typhus. Hut 25 had become a coffin, which the Americans, who freed the Lager a few days later, found crammed with hundreds of corpses.

His testimony for us today

The beatification of Father Januszewski is a source of joy and happiness for all Carmelites. The Church has considered one of our brethren an intercessor and an example, a valid witness for the universal Church. This is an occasion for Carmelites not only to feel that joy and to celebrate it, but also to reflect upon and to think deeply about Father Januszewski’s testimony, to find in his example keys to our own way of living today.

First of all, there is a good example in the biography of Father Januszewski of a selfless, quiet, silent life, founded upon deep prayer and service of others. Those who knew him insist that he was remarkably simple. Had it not been for his heroic death, he would probably have been forgotten, because he never stood out in extraordinary things.[11] But with that strength that grows from a life of prayer, acting in the presence of the Lord - something very typical and genuine in Carmelite spirituality - he gave himself up for others with the same simplicity with which he lived a quiet, hard-working life. A person educated in daily devotion generously offered his life when faced with arrest and the reality of the concentration camp. We could say that he succeeded in being faithful to his vocation in ordinary circumstances and, as a result, was also able to be just as faithful in truly extraordinary circumstances. Faithful in very little, he was faithful also in much (Lk 16, 10).

Father A. Urbanski, with whom he was joined both in religious life and in fate, writing to the Carmelite Curia in Rome from the camp during the forced quarantine following liberation, interpreted his death as follows:

Proh dolor R.P. Hilarius Januszewski, die 26.3.45, uno Mense ante liberationem, tanquam victima zelus sacerdotalis erga infectuose infirmos, mortuus est.[12]

As this century draws to a close, we are horrified by certain events that have taken place during it. We find the experience of the concentration camps in which Father Januszewski lost his life especially cruel and inhuman. However, there are situations even now that are, in a way, very similar: racial hatred, poverty and starvation, wars of all kinds, massacres, intolerant violent nationalist movements… The testimony of Father Januszewski invites the Carmelites of the twenty-first century to make a radical option for life, which nowadays is threatened in so many ways. He was able to do this in the most sublime way, giving up his own life for that of others.[13]

Father Januszewski’s example reminds us that Carmelites are called to vouch for life in the midst of a "culture of death", which shows itself in many different ways, not only in those regions of the world in which that "culture of death" is more obvious, but also in other areas where its presence is more subtle. Moreover, in the face of the temptation of "usefulness", of valuing human beings for what they produce, and eliminating those who are no longer useful and become a burden, Father Januszewski opted radically for the dying, the useless, those who apparently had nothing left to offer. With this action, he proclaimed and testified to the sacred value of human life, for itself and in itself. This witness given by Hilary Januszewski went to the ultimate limit, the giving of his own life.

We also find in Father Januszewski an especially interesting example for our experience of the Carmelite charism today. Januszewski, a man of silence and prayer, accustomed to talking to God, devoted to contemplation -like any good Carmelite - had no difficulty in finding the face of Christ in the weak, the needy and the suffering. In the awful conditions of Dachau, those with typhus fever, the dying, were the poorest of the poor and Father Januszewski, along with other priest volunteers, was willing to stay with them and end up dying with them and for them.

A life of intense prayer makes us more human and more capable of living in solidarity with others; it gives us the necessary intuition and sensitivity to discover the mysterious presence of the Lord in those who are weakest, in the midst of the tensions and contradictions of life. Like John in the boat on the Lake of Galilee, between the darkness of the passing night and the light of dawn, the Carmelite is called to proclaim, humbly but firmly: It is the Lord (Jn 21, 7).

Finally, the witness of Hilary Januszewski, soon to be called blessed must show Carmelites throughout the world the meaning of the international dimension of our Order. We must not forget that most of the patients Father Januszewski looked after were Russians (that is, from an enemy country). But this, seemingly, did not affect his decision. Overcoming national barriers, Father Januszewski offers us a true witness to universal fraternity, to reconciliation between enemy nations, and to peace.

Three years earlier, Blessed Titus Brandsma had ended a document, requested of him as part of the investigation into the opposition of Dutch Catholics to national-socialism, with the following words: God save Holland! God save Germany! Let God make these two nations walk in peace and freedom once again and recognise his Glory!

May the example and intercession of these two blessed Carmelites help us to enter the twenty-first century with a real spirit of service, peace and justice born out of a true and intense encounter with our Risen Lord.

Rome, 19 March 1999

Solemnity of St. Joseph

Fr Joseph Chalmers, O.Carm.

Prior General

Footnotes

1 R. TIJHUIS, Met Pater Titus Brandsma in Dachau: Carmelrozen 31-32 (1945/46) 18-21, 53-58, 80-85. The English translation may be consulted in: Dachau Eye-witness, in: AA.VV., Essays on Titus Brandsma [R. Valabek, ed.] (Rome 1985) 58-67.

2 F. MILLAN ROMERAL, Carmelitas en Dachau: las cartas del P. A. Urbanski, desde el lager, en el 50 aniversario de la liberación: Carmelus 42 (1995) 22-43.

3 A. URBANSKI, Duchowni w Dachau (Krakow 1945).

4 Cf. JUAN BOSCO DE JESÚS, Dos figuras de la Josefología en Polonia recientemente desaparecidas: PP. Alberto Urbanski, O.Carm. (1911-1985) y Estanislao Ruminski (1929-1984): Estudios Josefinos 40 (1986) 91-98.

5 Cf. Necrología (Obituary): Analecta O.Carm. 11 (1940-1942) 219; A. URBANSKI, Duchowni w Dachau, 61-66.

6 Cf. Necrología (Obituary): Analecta O.Carm. 12 (1943-1945) 230; A. URBANSKI, Duchowni w Dachau, 65-66.

7 Cf. Necrología (Obituary): Analecta O.Carm. 12 (1943-1945) 230; A. URBANSKI, Duchowni w Dachau, 61-66.

8 His photographs may be seen in the splendid photograph album published recently by the Carmelite Province of Poland: R. RÓG, Duch, Historia, Kultura (Krakow 1997) 68-69.

9 K. HEALY, Prophet of Fire (Rome 1990) 181-184 (Italian and Spanish versions available)

10 In the same sense, see the testimony of: F. KORSZYNSKI, Un vescovo polacco a Dachau (Brescia 1963) 125. This is the Italian translation (with a preface by the then Cardenal Montini) of Jasne promienie w Dachau (Poznan 1957).

11 Cf. K. HEALY, Prophet of fire (Rome 1990) 181-184.

12 F. MILLAN ROMERAL, Carmelitas en Dachau: las cartas del P. A. Urbanski, desde el lager, en el 50 aniversario de la liberación: Carmelus 42 (1995) 37. In another letter, written in German, he insists on this: "Als Opfer zelus sacerdotalis ist er gestorben" (ibid. 42).

13 Cf. R. VALABEK, Greater Love Than This... Father Hilary Januszewski, O. Carm.: Carmel in the World 30 (1991) 209-216.